Design Patterns

Introduction

Design patterns are classified as three groups.

- Creational Patterns

- Abstract Factory - Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.

Factories and products are the key elements to Abstract Factory pattern. Also the word families used in the definition distinguishes Abstract Factory pattern from other creational patterns, which involve only one kind of object. - Builder - Separates object construction of a complex object from its representation so that the same construction process can create different representation.

One example is the making different types of teas such as tea with sugar, tea with milk, and just a regular tea. The process of making those teas share common processes: boil water and put tea bags. Depending on the types, the added processes are such as put sugar, put milk, or nothing.

- Builder: Builder is responsible for defining the construction process for individual parts. Builder has those individual processes to initialize and configure the product (teas).

- Director: Director takes those individual processes from the builder and defines the sequence to build the product.

- Product: Product is the final object which is produced from the builder and director coordination.

- Factory Method- Define an interface for creating an object, but let subclasses decide which class to instantiate.

Factory Method lets a class defer instantiation to subclasses. To name the method more descriptively, it can be named as Factory and Product Method.

If we want to create a Mac style scroll bar, we can write a code like this:ScrollBar *sb = new MacScrollBar;

But if we're going to make it work across any platform, we should write a code something similar to this:ScrollBar *sb = guiFactory->CreateScrollBar();

Because guiFactory is an instance of MacFactory class, the CreateScrollBar returns a new instance of Mac style scrollbar. The MacFactory itself is a subclass of GUIFactory which is an abstract class where general interface for widgets.

So, the product objects here, are widgets.

The instance variable guiFactory is initialized as:GUIFactory *guiFactory = new MacFactory;

- Prototype - Specify the kind of objects to create using a prototypical instance, and create new object by copying this prototype.

- Singleton - Ensure a class only has one instance, and provide a global point of access to it.

- Abstract Factory - Provide an interface for creating families of related or dependent objects without specifying their concrete classes.

- Structural Patterns

- Adapter - Convert the interface of a class into another interface clients expects. Adapter lets classes work together that couldn't otherwise because of incompatible interfaces.

- Bridge - Separates an object's abstraction from its implementation.

- Composite - Compose objects into tree structures to represent part-whole hierarchies. Composite lets clients treat individual object and compositions of object uniformly.

- Decorator - Add responsibilities to objects dynamically. Decorators provide a flexible alternative to subclassing for extending functionality.

Example: TextView

A TextView object that displays text in a window. When we need a scrollbar we just use a ScrollDecorator or when we need a border around the text area, we just use a BorderDecorator to add border.

We simply compose the decorators with the TextView to produce the desired result. - Facade - A single class that represents an entire subsystem.

- Flyweight - A fine-grained instance used for efficient sharing.

- Proxy - An object representing another object.

- Behavioral Patterns

- Mediator - Defines simplified communication between classes.

- Memento - Capture and restore an object's internal state.

- Interpreter - A way to include language elements in a program.

- Iterator - Sequentially access the elements of a collection.

- Chain of Responsibility - A way of passing a request between a chain of objects.

- Command - Encapsulate a request as an object, thereby letting you parameterize clients with different requests, queue or log requests, and support undoable operations.

- State - Alter an object's behavior when its state changes.

- Strategy - Define a family of algorithm, encapsulate each one, and make them interchangeable. Strategy lets algorithm vary independently from clients that use it.

Example: Duck class with encapsulated behaviors such as Flybehavior and Quackbehavior. - Observer - Define a one-to-many dependency between objects so that when one object changes state, all its dependents are notified and updated automatically.

- Subject: knows its observers.

- Observer: defines an updating interface for object that should be notified of changes in a subject.

- Template Method - Define the skeleton of an algorithm in an operation, deferring some steps to subclasses. Template Method lets subclasses redefine certain steps of an algorithm without changing the algorithm's structure.

- Visitor - Defines a new operation to a class without change.

Aggregation and composition are both strong forms of association. They describe relationship between a whole and as its parts. So, instead of a has-a relationship as a simple association, we are dealing with a relationship says is part or reading the relationship in the other direction, is made up of.

Examples of these kind of relationship:

- Orchestra: Musician

Orchestra is made up of Musicians

or Musician is part of Orchestra

- Brochure: Product

Brochure is made up of Products

or Product is part of Brochure

- Building: Room

Building is made up of rooms

or Room is part of Building

Composition is even stronger relationship than aggregation. To test if we are dealing with composition, use no sharing rule for composition: part can belong to only one whole.

For the #1 and #2, part (Musician/Product) can belong only one (Orchestra/Catalog) whole? Yes! But for #3, room can belong to more than one building. No! No sharing rule applies to this case. So, the relationship #3 is better described by composition than by aggregation.

Besides the no sharing rule, another the rule for composition is: if the whole is destroyed, is the part that makes it up also destroyed?

Only the case #3 follows the additional composition rule. If orchestra breaks it up, will musicians be destroyed? No!

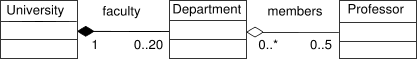

Code Example: A university owns various departments, and each department has a number of professors. If the university closes, the departments will no longer exist, but the professors in those departments will continue to exist. Therefore, a University can be seen as a composition of departments, whereas departments have an aggregation of professors. In addition, a Professor could work in more than one department, but a department could not be part of more than one university.

- University - Department : composition: ownership: destroyed with the whole: strong has a relationship

The composite object takes ownership of the component. This means the composite is responsible for the creation and destruction of the component parts. An object may only be part of one composite. If the composite object is destroyed, all the component parts must be destroyed.

Composition enforces encapsulation as the component parts usually are members of the composite object:

class University { ... private: Department faculty[20]; - Department - Professors: aggregation: no ownership: may outlive: component may still have weak has a relationship

In aggregation, the object may only contain a reference or pointer to the object. The object may not have lifetime responsibility for the reference or pointer:class Department { ... private: // Aggregation Professor* members[5]; ... };

Complete code example:

class Professor;

class Department

{

...

private:

// Aggregation

Professor* members[5];

...

};

class University

{

...

private:

Department faculty[20];

...

create dept()

{

....

// Composition

faculty[0]= Department(....);

faculty[1]= Department(....);

....

}

};

Source of the code and diagrams: wiki

In UML, composition is depicted as a filled diamond and a solid line. It always implies a multiplicity of 1 or 0..1, as no more than one object at a time can have lifetime responsibility for another object.

The more general form, aggregation, is depicted as an unfilled diamond and a solid line. The image above shows both composition and aggregation.

The UML puts some notations to our software model. Usually, a single class is represented with a box that is divided into three parts:

- The upper section contains the class name.

- The middle section has lists attributes of the class.

- The lower section lists methods of the class.

The members of the class in the middle and lower sections can be prefixed with a symbol to indicate the access level or visibility:

- +: a public member

- -: a private member

- #: a protected member

We can tell the relationships between classes by using various styles of connecting lines and arrowheads:

- Association: A simple dependency between two classes where neither owns the other, indicated as a solid line. Association can be directional, shown with an open arrowhead (">").

- Aggregation: A has-a, or whole/part, relationship where neither class owns the other, indicated as a solid line with a hollow diamond.

- Composition: A has-a relationship where the lifetime of the part is managed by the whole. This is shown as a solid line with a filled diamond.

- Generalization: A subclass relationship between classes, represented as a hollow triangle arrowhead.

Each side of a relationship can also be annotated to define its multiplicity. This lets us specify whether the relationship is one to one, one to many, or many to many:

- 0..1 = zero or one instance

- 1 = one instance

- 0..* = zero or more instances

- 1..* = one or more instances

The two most common ways for reusing functionality in object-oriented systems are class inheritance and object composition.

Class Animal{};

Class Cat : public Animal{};

In this simple example, class Cat is related to class Animal by inheritance, because Cat is derived from Animal.

In the example below, class Cat is related to class Animal by composition, because Cat has an instance variable that holds a pointer to a Animal object. Classes like in the example, Cat is sometime called front-end class and Animal is called the back-end class. In a composition relationship, the front-end class holds a pointer in one of its instance variables to a back-end class.

class Animal

{};

class Cat

{

private:

Animal *animal;

};

Class inheritance lets us define the implementation of one class in terms of another's. Object composition is an alternative to class inheritance. Here, new functionality is obtained by composing object. In this case, no internal details of objects are visible (black-box) contrary to the class inheritance where the internals of parent classes are often visible (white-box) to subclasses.

While class inheritance makes it easier to modify the implementation being used, the implementation of a subclass becomes so bound up with the implementation of its parent class. As a result, any change in the parent's implementation will force the subclass to change.

Leet's look at the following example:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Animal

{

public:

int makeSound() {

cout << "Animal is making sound" << endl;

return 1;

}

private:

int ntimes;

};

class Cat : public Animal

{};

int main()

{

Cat *cat = new Cat();

cat->makeSound();

return 0;

}

Since Cat inherits (reuses) Animal, the output get is:

Animal is making sound

However, if we want to change the makeSound() method of parent class, like this:

Sound *makeSound(int n) {

cout << "Animal is making sound" << endl;

return new Sound;

}

Our main() routine should be changed as well even though we're not using Animal but Cat.

Here is the new code we had to come up with:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Sound{};

class Animal

{

public:

Sound *makeSound() {

cout << "Animal is making sound" << endl;

return new Sound;

}

};

class Cat : public Animal

{};

int main()

{

Cat *cat = new Cat();

cat->makeSound();

return 0;

}

Composition provides an alternative way for Cat to reuse Animal's implementation of makeSound(). Instead of inheriting Animal, Cat can hold a pointer to a Animal instance and define its own makeSound() method that simply invokes makeSound() on the Animal. Here's the code:

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Animal

{

public:

int makeSound() {

cout << "Animal is making sound" << endl;

return 1;

}

};

class Cat

{

private:

Animal *animal;

public:

int makeSound() {

return animal->makeSound();

}

};

int main()

{

Cat *cat = new Cat();

cat->makeSound(3);

return 0;

}

By using composition, the subclass becomes the front-end class, and the superclass becomes the back-end class. With inheritance, a subclass automatically inherits an implementation of any non-private superclass method that it doesn't override. With composition, however, the front-end class must explicitly invoke a corresponding method in the back-end class from its own implementation of the method. This explicit call is sometimes called forwarding or delegating the method invocation to the back-end object.

The composition approach to code reuse provides stronger encapsulation than inheritance, because a change to a back-end class needn't break any code that relies only on the front-end class. In other words, inheritance exposes a subclass to details of its parent's implementation, it's often said that "inheritance breaks encapsulation".

By changing the return type of Animal's makeSound() method from the previous example doesn't force a change in Cat's interface and therefore needn't break our main() code.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Sound{};

class Animal

{

public:

Sound* makeSound() {

cout << "Animal is making sound" << endl;

return new Sound();

}

};

class Cat

{

private:

Animal *animal;

public:

Sound* makeSound() {

return animal->makeSound();

}

};

int main()

{

Cat *cat = new Cat();

cat->makeSound();

return 0;

}

This example shows that the ripple effect caused by changing a back-end class stops (or at least can stop) at the front-end class. Although Animal's makeSound() method had to be updated to accommodate the change to Animal, our main()required no changes.

Object composition helps us keep each class encapsulated and focused on one task. Our classes and class hierarchies will remain small and will be less likely to grow and become unmanageable.

However, a design based on object composition will have more objects (if fewer classes), and the system's behavior will depend on their (remote) interrelationships instead of being defined in one class.

Favor object composition over class inheritance.

Delegation makes composition as powerful for reuse as inheritance. With delegation, two objects are involved in handling a request. A receiving object delegates operations to its delegate, which is similar to the case when subclass defers requests to parent class.

As shown in the following code, rather than making Window a subclass of Rectangle, the Window class is reusing the behavior of Rectangle by keeping a Rectangle instance variable rectangle and delegating Rectangle-specific behavior to it. So, though the Window is not a Rectangle but it has a Rectangle. If we had used inheritance, the Window would have had the behavior. But now Window must forward request to its Rectangle instance explicitly.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Rectangle

{

private:

double height, width;

public:

Rectangle(double h, double w) {

height = h;

width = w;

}

double area() {

cout << "Area of Rect. Window = ";

return height*width;

}

};

class Window

{

public:

Window(Rectangle *r) : rectangle(r){}

double area() {

return rectangle->area();

}

private:

Rectangle *rectangle;

};

int main()

{

Window *wRect = new Window(new Rectangle(10,20));

cout << wRect->area();

return 0;

}

With an putput:

Area of Rect. Window = 200

The main advantage of delegation is that it makes it easy to compose behaviors at run-time. For example, the Window can become circular at run-time as shown in the following code.

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class Shape

{

public:

virtual double area() = 0;

};

class Rectangle : public Shape

{

private:

double height, width;

public:

Rectangle(double h, double w) {

height = h;

width = w;

}

double area() {

return height*width;

}

};

class Circle : public Shape

{

private:

double radius;

public:

Circle(double r) {

radius = r;

}

double area() {

return 3.14*radius*radius;

}

};

class Window

{

public:

Window (Shape *s):shape(s){}

double area() {

return shape->area();

}

private:

Shape *shape;

};

int main()

{

Window *wRect = new Window(new Rectangle(10,20));

Window *wCirc = new Window(new Circle(20));

cout << "rectangular Window:" << wRect->area() << endl;

cout << "circular Window:" << wCirc->area() << endl;

return 0;

}

Delegation is a good choice only when it simplifies more than it complicates. In general, software which is dynamic and parameterized is harder to understand that more static software and there is also run-time inefficiency issue. So, it should be wisely used, for instance, by following standard design patterns like Strategy pattern.

Good design exhibits loose coupling and high cohesion.

- Coupling

A measure of the strength of interconnectivity between components: the degree to which each component depends on other components. In other words, for a given two components (A and B), how much code in B should change if A changes.- Size

Relates to the number of connections between components (classes, methods, arguments, etc.). For instance, a method with fewer parameters is more loosely coupled to components that call it. - Visibility

This refers to the prominence of the connection between components. As an example, changing a global variable in order to change the state of another component is a poor level of visibility. - Intimacy

This relates to the directness of the connection between components. If A is coupled to B and B is coupled to C, then A is indirectly coupled to C. For example, inheriting from a class is tighter than including class as a member variable (composition) because inheritance also provides access to all protected members of the class. - Flexibility

This refers to the ease of changing the connection between components. If a method's signature of a class A needs to change so that B can call it, how easy is it to change that method and all dependent code.

- Size

- Cohesion

A measure of how strongly related the functions of a single component are.

If class A only needs to know the name of the class B but not need to call any methods of class B, then the class A does not depend on the full declaration of B. In that case, we just use forward declaration for class B so that we can reduce the coupling between those two classes:

class B; // forward declaration

class A:

{

public:

A();

void setObj(B *objB);

B *getObj() const;

private:

B *mObj;

};

In the example above, if the associated .cpp file simply stores (*mObj) and returns the B pointer (B*), then it does not need #include "B.h". So, in this case, the A class can be decoupled from the implementation of B

We can reduce coupling between classes by using non-member function instead of member functions. Let's look at the following sample.

class Student

{

public:

void printID() const;

int getID() const;

...

protected:

...

private:

int id;

};

We can modify the class like this:

class Student

{

public:

int getID() const;

...

protected:

...

private:

int id;

};

void printID(const Student &obj;);

With the latter class design, we can reduce coupling because the function printID() can only access the public methods of Student. But in the former form where printID() is a member function, it can also access all of the private and protected members, and other members of Student, as well as any protected members of base class if any.

Using the non-member function, non-friend form means that the function is not coupled to the internals of the class. As a result, it is less likely to break when the internals of Student are changed.

We see this approach a lot in the STL. For example, the STL algorithms such as std::for_each() and std::unique(), which are declared outside of each container class.

The following code is for chatting session log. It accepts chat event,it takes an object that describes a user and the message from the user. This information is processed with the timestamp, and then added to a list.

#include "ChatCustomer.h"

#include <string>

#include <vector>

class CustomerChatLog

{

public:

bool addMessage(const ChatCustomer &customer;, const std::string &msg;);

int getCount() const;

std::string getMessage(int index);

private:

struct ChatEvent

{

ChatCustomer mCustomer;

std::string mMessage;

size_t mTimeStamp;

};

std::vector mChatEvent;

};

Then, we can use getCount() method to find how many chat text events have occurred. The getMessage() method returns an event like this:

John Doe[13:04]: Hi

When we look at the design more carefully, the CustomerChatLog class is coupled with the ChatCustomer class. The ChatCustomer class may be a very heavy class that can cause many dependencies. So, we can try to modify the CustomerChatLog class design a little bit. Actually, the CustomerChatLog class does not use lots of members of ChatCustomer class, instead it uses when we call ChatCustomer::getName() method. So, one possible solution to this coupling problem is to pass just the name of the customer to CustomerChatLog class not the ChatCustomer object itself as in the following version:

//#include "ChatCustomer.h"

#include <string>

#include <vector>

class CustomerChatLog

{

public:

bool addMessage(const std::string &customer;, const std::string &msg;);

int getCount() const;

std::string getMessage(int index);

private:

struct ChatEvent

{

std::string mCustomerName;

std::string mMessage;

size_t mTimeStamp;

};

std::vector mChatEvent;

};

Though this approach induced redundancy in terms of the customer's name, but it breaks the dependencies between two classes.

We can reduce coupling related to the event notification.

Let's think about Massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG). Each player is represented by Universally unique identifier (UUID). But players want to see the names of other players, not UUID strings. To store the corresponding UUID and name, the system, therefore, implements a player name archive, NameArchive.

Suppose, the class that manages the game preparation, GamePrep, is trying to display the name of each player. Here are the operations of displaying the names:

- The GamePrep class calls NameArchive::requestName()

- The NameArchive sends a request to the game server for the name of the player with this UUID.

- The NameArchive receives the name from the server.

- The NameArchive calls GamePrep::setPlayerName()

The GamePrep, however, depends on NameArchive to call the NameArchive::requestName() method, and NameArchive depends on GamePrep to call the GamePrep::setPlayerName() method. This is not a loosely coupled design, rather it's tight. Suppose, we need the name, in the game, not in the preparation settings. Then, probably we need Game::setPlayerName() method, which makes the design more tight.

Here is the solution addressing the coupling issues. Let the GamePrep and Game classes register as subscribers so that they can get updates from the NameArchive. Then, the NameArchive will notify to the subscribers without having a direct dependency on GamePrep and Game classes.

- Callbacks

A callback is a pointer to a function within Module_A that is passed to Module_B so that Module_B can invoke the function in Module_A. But Module_B does not know anything about Module_A, and it has no include or does not have any dependency on Module_A. Therefore, callbacks are particularly useful to allow low-level code to execute high-level code that it cannot have any link dependency. That's why callbacks are a popular way of breaking cyclic dependencies in huge projects.

Sometimes, it is useful to provide a closure with the callback functions. The closure is a piece of data that Module_A passes to Module_B, and it is sort of states.

#include <string> class Module_B { public: typedef void (*CallbackType)(const std::string &name;, void *data); void setCallback(CallbackType cb,void *data); private: CallbackType mCallback; void *mClosure; };Then the Module_B can invoke the callback function with something like this:

if(mCallback) { (*mCallback) ("Hi", mClosure); }Implementing a callback to a static C++ member function is done the same way as in C. This is because static member functions do not need an object to be invoked on and thus have the same signature as a C function with the same calling convention, calling arguments and return type.

However, using callbacks in C++ has one implication. In other words, it is non-trivial to use a method as a callback because the this pointer of the object also needs to be passed. Actually, boost::bind in Boost library provides a solution to this issue. It implements functors (functions with state) that can be realized in C++ as a class with private member variables to hold the state and an overloaded operator() to execute the function.

. - Observers

As mentioned above, implementing callbacks in C++ is not simple. But by using Observer Pattern, we can minimize coupling in our software design.

- Signal/Slot (Qt) and boost::signals

Callbacks and observers are created to do specific task, and the mechanism to use them is usually defined within the objects that need to perform the actual callback.

An alternative approach is to construct a centralized control to send events between unconnected parts of the system. So, the sender does not have to know about the receiver beforehand, which lets us reduce coupling between the sender and the receiver. Qt's signal/slot concept is a generic way to allow any event, such as a mouse press or a button click, to be sent to any interested method to act upon. Boost's boost::signals and boost::signals2 are also available.

This section will show how we can hide implementation details using a timer. The following examples will evolve from a code for Windows, and then it will be extended to Linux system, and finally to a code that hides platform dependent implementation.

First, we have a code for Windows as below:

// timer.h

#include <Windows.h>;

class Timer

{

public:

explicit Timer(double);

~Timer();

private:

double elapsedTime() const;

DWORD mStartTime;

double mDuration;

};

// timer.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "timer.h"

Timer::Timer(double d) : mDuration(d)

{

mStartTime = GetTickCount();

}

Timer::~Timer()

{

while(elapsedTime() < mDuration) ;

std::cout << mDuration << " sec elapsed" << std::endl;

}

double Timer::elapsedTime() const

{

return (GetTickCount() - mStartTime)/1000 ;

}

// main.cpp

#include "timer.h"

int main()

{

double wait = 5;

Timer *pTimer = new Timer(wait);

delete pTimer;

return 0;

}

With an output:

5 sec elapsed

The code above can be extended to Linux systems as shown below:

// timer.h

#ifdef WIN32

#include <Windows.h>

#else

#include <sys/time.h>

#endif

class Timer

{

public:

explicit Timer(double);

~Timer();

private:

double elapsedTime() const;

#ifdef WIN32

DWORD mStartTime;

#else

struct timeval mStartTime;

#endif

double mDuration;

};

// timer.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "timer.h"

Timer::Timer(double d) : mDuration(d)

{

#ifdef WIN32

mStartTime = GetTickCount();

#else

gettimeofday(&mStartTime;, NULL);

#endif

}

Timer::~Timer()

{

while(elapsedTime() < mDuration) ;

std::cout << mDuration << " sec elapsed" << std::endl;

}

double Timer::elapsedTime()

{

#ifdef WIN32

return (GetTickCount() - mStartTime)/1000 ;

#else

struct timeval endTime;

gettimeofday(&endTime;,NULL);

return endTime.tv_sec+(endTime.tv_usec/1000000.0)-

(mStartTime.tv_sec+(mStartTime.tv_usec/1000000.0)) ;

#endif

}

For linux, we used

int gettimeofday(timeval *tp, NULL)

The function gettimeofday()

gets the time of day. The parameter must be a pointer to a previously declared timeval variable

(or in C, a struct timeval variable).

This struct type is also defined in

// timer.h

class Timer

{

public:

explicit Timer(double);

~Timer();

private:

class Implementation;

Implementation *pImpl;

};

The above header file, timer.h, does not have any platform specifics, and we cannot see any private members in the header file. In other words, private members are now completely hidden from our public interface. This allows us to keep our implementation details hidden, and our public header files are cleaner. So, as a result, they can be read more easily.

However, when we must create an object of Timer::Implementation in the constructor, and destroy it in the destructor. Another thing than makes it more complicated is we have to access all the private members using pImpl pointer. But the cleaner API outweighs the overload.

// timer.cpp

#include "timer.h"

#include <iostream>

#ifdef WIN32

#include <Windows.h>

#else

#include <sys/time.h>

#endif

class Timer::Implementation

{

public:

double elapsedTime()

{

#ifdef WIN32

return (GetTickCount() - mStartTime)/1000 ;

#else

struct timeval endTime;

gettimeofday(&endTime;,NULL);

return endTime.tv_sec+(endTime.tv_usec/1000000.0)-

(mStartTime.tv_sec+(mStartTime.tv_usec/1000000.0)) ;

#endif

}

#ifdef WIN32

DWORD mStartTime;

#else

struct timeval mStartTime;

#endif

double mDuration;

};

Timer::Timer(double d):pImpl(new Timer::Implementation())

{

pImpl->mDuration = d;

#ifdef WIN32

pImpl->mStartTime = GetTickCount();

#else

gettimeofday(&(pImpl->mStartTime), NULL);

#endif

}

Timer::~Timer()

{

while(pImpl->elapsedTime() < pImpl->mDuration) ;

std::cout << pImpl->mDuration << " sec elapsed" << std::endl;

delete pImpl;

pImpl = NULL;

}

The class design of the previous section has some good things:

- Declaring it as a nested class prevents from polluting the code with platform specifics.

- Declaring it as private makes the public API clean.

However, the design has some weakness at copying. Because compiler will create a copy constructor and assignment operator unless we explicitly define it, the objects can have pointers (pImpl) pointing to the same object of type Implementation. The will cause crash when several objects may try to delete the same object in their destructor.

If we do not want make our class to be copyable, we can modify the timer.h as below:

// timer.h

class Timer

{

public:

explicit Timer(double);

~Timer();

Timer(const Timer &); // copy constructor

Timer &operator;=(const Timer &); // assignment operator

class Implementation;

private:

Implementation *pImpl;

};

By declaring the copy constructor and assignment operator, we can prevent our class from being copied.

See other ways of making a class non-copyable.

See boost::scope_ptr.

- Software Development Methodology

- GIT and GitHub on Windows - 1. Installation

- GIT and GitHub on Windows - 2. add/status/log

- GIT and GitHub on Windows - 3. commit and diff

- GIT and GitHub on Windows - 4. GitHub Account and SSH

- GIT and GitHub on Windows - 5. Uploading to GitHub

- GIT and GitHub on Windows - 6. GUI

- GIT and GitHub on Windows - 7. Branching, Merging, Cloning, and Forking

Ph.D. / Golden Gate Ave, San Francisco / Seoul National Univ / Carnegie Mellon / UC Berkeley / DevOps / Deep Learning / Visualization